The Washington Post

When Linda Price arrived on campus at Wayland Baptist College as a freshman in 1966, she encountered all of the prejudice against women that could be expected at a small, religious school in a farming town in the conservative Texas Panhandle.

At Wayland, different sets of curfews meant she had an earlier bedtime than her male classmates; strict dress codes restricted her freedom to choose what she looked like; and unlike the men on campus, when she wanted to get married her senior year, she had to get permission from the administration so that she wouldn’t lose her athletic scholarship.

But there was one place where Price and her female classmates were treated as equals: on the basketball court.

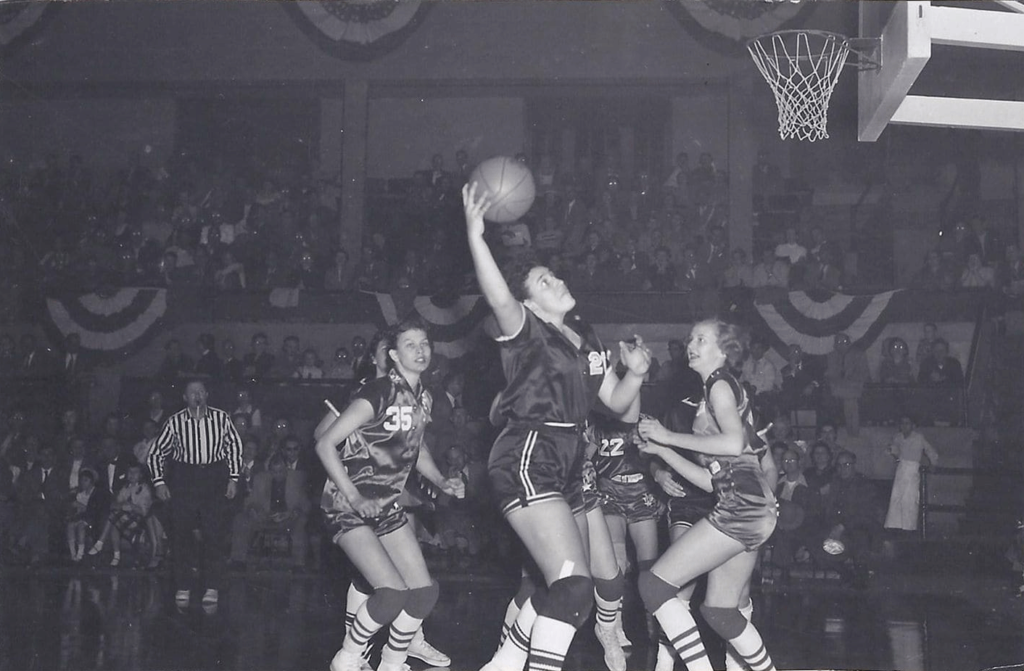

There, well before the passage of Title IX in 1972 prohibited sex discrimination in education and before the NCAA began sponsoring women’s basketball a decade later, the Wayland Baptist Flying Queens ruled. The small school nestled between Lubbock and Amarillo in Plainview, Tex., fielded a powerhouse women’s basketball team for decades in the mid-20th century, winning 131 straight games from 1953 to 1958 — 20 games more than Connecticut women’s basketball’s historic 111-game streak that ended in last year’s NCAA tournament. They collected 10 national AAU titles from 1954 to 1975.

The Queens, who find out Saturday whether they will be inducted into the Naismith Memorial Basketball Hall of Fame when the Class of 2018 is announced in San Antonio, were trailblazers in women’s basketball. Not only were they talented enough to spawn Women’s Basketball Hall of Fame players who competed for the United States internationally, but they were uncommonly well-funded and glamorous, decades before large universities put any real fundraising or marketing muscle behind women’s basketball.

Thanks to sponsor Claude Hutcherson and his wife, Wilda, who made their fortune in aviation, the Queens flew to games in four small, private planes. They arrived in custom-made warmup suits at packed gyms across the Southwest and delighted crowds with warmup routines handed down from the Harlem Globetrotters and set to the tune of “Sweet Georgia Brown.”

“People asked for autographs when we got off the plane, it was like being rock stars,” said Price, who played for the Queens from 1966 to 1969.

Wayland Baptist recruited players mainly from rural, often poor communities in Texas, Oklahoma and Iowa, awarded athletic scholarships and provided scores of women who otherwise wouldn’t have been able to go to college the chance to further their education.

“I guess that’s why I’m hoping so much for Naismith to document this,” Price, who now works as a health care consultant in Houston, said in a recent telephone interview. “There’s this sort of bias nationally about what Texas or Oklahoma is, and a lot of it is true, there’s no getting around that. . . . There were so many differences in the ways women and men were treated, and in today’s world, there would be another name for that — discrimination. But on the basketball court, well, our name was the Queens and we were treated like it.”

Ambassadors for the school

Women have been playing basketball at Wayland Baptist — which in 1981 attained university status and became known as Wayland Baptist University — in some form or another since the school opened its doors in 1910, primarily because women from the region had grown up with the sport and they saw no reason to stop once they entered college.

“It was really, all along, women asking administrators, ‘Let us play, let us play,’ and they did,” Price said.

There was less of a stigma around basketball as a masculine activity in the rural farming communities surrounding Plainview, where boys and girls grew up doing manual labor together.

“The size of my town was 300 people, so school, sports or the church was the only thing you had to do. There wasn’t even a drive-in to go get a Coke,” said Cherri Rapp, who played for the Queens beginning in 1968 and spent six seasons on the U.S. women’s national team.

“Most all of our players came from farming communities in the Texas Panhandle, Oklahoma, or Iowa. Those were the only three states that really had a lot of basketball. And in Texas, most of the big schools didn’t play. There’s no basketball in Amarillo or Lubbock or in Dallas or San Antonio. They didn’t have teams. Only the little, itty-bitty schools had teams.”

Few of those small colleges had teams as well-known as Wayland’s. Before the team’s win streak brought local fame, the Flying Queens’ renown was largely due to the college’s enterprising and open-minded president, J.W. Marshall. Among other progressive efforts, Marshall integrated the campus in 1951 — three years before Brown v. Board of Education helped end segregation in public schools — as he tried to expand Wayland into an international college.

That expansion included the promotion of the women’s basketball team, whose players Marshall viewed as excellent ambassadors for the school. The Wayland Baptist team transitioned from a recreational club sport to an AAU team in 1947, and in 1948, when the university was struggling to support both a men’s and women’s team, Marshall secured a sponsorship for the women from the local wheat mill.

Originally named the Harvest Queens, they became the Flying Queens after Marshall asked Hutcherson, a Wayland alumnus and owner of the Hutcherson Air Service, to sponsor the team in 1951.

The Hutchersons became more than benefactors — they took care of the women and opened their many homes to players whenever they could.

Claude Hutcherson died in 1977, but Wilda’s dedication to the program never waned, and she still resides in Plainview with her second husband. After Claude died, she married Harley Redin, the man who coached the Flying Queens from 1955 until 1973 and led the team to six AAU national titles and six second-place finishes.

It was Wilda, who celebrated her 97th birthday this month, who had always made sure the Queens were well-dressed.

“Well, it was no easy job to get all the Queens dressed properly because they were all different sizes — we had short girls and tall girls and girls that were some kind of difficult,” Wilda Hutcherson said. “I know one time they were green, one time they were blue — the coats and the trousers were all one color. We wanted a team that the college could be proud of and that we could be proud of. They did look nice when they got off the airplane.”

As the women’s team became more and more famous throughout the Panhandle, the men’s team played without a sponsor and traveled to games by bus.

“It was kind of really sad about the poor little men!” Rapp said. “It’s just the opposite from what happened in most schools where the boys get the money and the girls are just the sideshow. The guys were really pretty good about it. We got along . . . but they didn’t have what we had.”

A life-changing experience

Price was 7 years old when she first heard about the Queens after the team’s winning streak had spread the Queens’ name all the way to Southern Oklahoma.

For Price, basketball had just been a pastime, but she had grown up with three siblings in a one-room house without indoor plumbing or electricity. When she discovered Wayland Baptist would pay for college if you were good enough to make the team, basketball became her passion.

“I immediately knew that was my dream. I was going to be a Flying Queen,” Price said. “It was going to be my way out.”

Those early teams from the ’50s helped inspire a generation of girls in rural Texas and Oklahoma to pursue basketball. The Queens traveled to AAU games in which they played semiprofessional teams sponsored by businesses such as Hanes Hoisery and Nashville Business College, Wayland’s rival in the 1950s and ’60s, and games were competitive and entertaining. With their ability to award scholarships, Wayland Baptist became the most enticing option for the best players in the region.

As many as 50 girls showed up at tryouts each year, so much so that the school created a freshman team — the Queen Bees — that played local high school teams ahead of the Flying Queens games.

Many Queens from across decades echo Price’s story: Being able to play basketball at Wayland was a life-changing experience, and many credit the leadership and confidence they gained as the foundation for successful careers.

Legendary former Texas Tech coach Marsha Sharp — who took the Red Raiders to 18 NCAA tournament appearances and won the 1993 national title with Sheryl Swoopes leading the way — says she owes so much of her success to Redin’s decision to allow her to coach the Queen Bees as a junior in college in 1972 after she played on the team for two years.

“It makes it even more remarkable really that I wasn’t a great player, but I was able to be around greatness every day. And it probably helped me understand what that looked like and how hard you had to work to make that happen, so that when I did get my job at Texas Tech, I sort of had some point of reference,” Sharp said. “There were dozens of players who came out of Wayland who became college coaches or were some of the better high school coaches, particularly in the states of Texas and Oklahoma. It was such a far-reaching trickle.”

Nowadays, the Queens compete with other small private schools in the NAIA, which is a smaller college athletic association that lacks the NCAA’s economic might. As women’s collegiate basketball has grown and benefited from the revenue big-time football and men’s basketball can provide, larger universities have overshadowed Wayland’s accomplishments.

But Price tries to make sure the current Queens know the program’s trailblazing history, and is hoping that an induction into the Hall of Fame helps keep the Queens’ memory alive.

“It’s been remarkable, talking to the current Queens. I thought they were just going to say like, ‘Who’s this old lady talking at us?’ But no, it’s just the opposite,” Price said. “It feels like a sisterhood. They tell me, ‘We want what y’all had.’ ”

MORE AT THE LINK: BEFORE THERE WAS U-CONN., THE WAYLAND BAPTIST QUEENS RULED THE BASKETBALL COURT